What natural language is most similar to mathematical notation ?

What natural language is most similar to programming languages ?

I hear legal English is pretty close.

20101231

20101230

20101228

Year of the Leak

2010 is the year of the leak. From the Afghanistan and Iraq war diaries, to Cablegate, and the upcoming revelations about Bank of America, the website Wikileaks has driven the media debate, challenged American foreign policy, and proposed a new way to control governments and corporations. The hyperbole surrounding Wikileaks has been tremendous. Senators have demand the head of Julian Assange on the Senate floor, while Assange has compared himself to Martin Luther King and Gandhi. The allegations of rape, treason, and espionage make for a dramatic tale, but there are important questions to be asked. Is the absolute transparency of Wikileaks truly good for democratic governance? What balance of openness and privacy should we strive for in society? And what comes after Wikileaks?

Public transparency is one of the cornerstones of democracy. Citizens must know what the government does in their name, must know that public figures are capable and honest, so that if they are not they can be replaced. The traditional organ of transparency are the press. In the worlds of Thomas Jefferson, “Our liberty cannot be guarded but by the freedom of the press, nor that be limited without danger of losing it.” The press exists to monitor politicians, and inform the public, but it is also dependent on public officials for leads and quotes, and beholden to commercial advertising. The entertaining, familiar press is a fixture, but is less credible than ever before. There is a widespread sense among Americans that the news is not telling them the truth, that stories are slanted and incomplete.

Into this gap steps Wikileaks, with a radically different view of how information and the public should work. Wikileaks demands that all information be publicly accessible, that governments and corporations should be completely transparent, and that those who do not abide by these rules will be punished. But despite similar techniques, do not confused Wikileaks with the press; Wikileaks is a political organization with revolutionary fundamentally antithetical to the structure of contemporary society.

Julian Assange is a deep, if unconventional political theorist, and at the heart of Wikileaks is his idea of the authoritarian conspiracy. Assange believes that the world is ruled by conspiracies, not in the “9-11 was an inside job, aliens exist, the Queen of England is a reptoid” way, but in a much more formal, mathematical idea that there are networks of power and influence which exert a great deal of control on events, to the detriment of people in general. This authoritarian conspiracies are the real structure of government, senior civil servants, politicians, industrialists and tycoons, and they collaborate to run the world system.

Assange wants to kill this conspiracy, and Wikileaks is his tools. Conspiracies and networks are hard to eliminate, there is no central commander to decapitate, new members rise up from the ranks. The continued battle against Al Queda shows how difficult it is to destroy a conspiracy. Instead of waging war on the powerful, Assange has targeted its infrastructure, the network of trust that allows the global authoritarian conspiracy to coordinate its actions. There is no specific information available to Wikileaks, rather its existence and ability to expose and embarrass authoritarian conspiracies forces them to spend time and energy on internal security, reduces the ability of conspirators to trust one another, and ultimately drives the conspiracy into paralysis. An authoritarian conspiracy that cannot communicate, cannot think, cannot act, and will ultimately be destroyed.

Is the American government an authoritarian conspiracy, as Assange describes them? From certain viewpoints, yes. The American government often acts in a secret, and has lied, deceived, and killed in the name of small, wealthy interests before. It represents only 307 million of the nearly 7 billion people on this planet. But on the other hand, domestic funding is publicly accountable, and the U.S. often acts the 'global policeman' to stop rogue states and weapons of mass destruction.

As Jaron Lanier lays out in an excellent essay, the internet is at its basis binary, on or off, totally open or completely closed. This feature is built into the core of the hardware that runs the internet, and is how Wikileaks is so successful. A poorly secured government network (SIPRNet) was penetrated by one of the three million users who had access. Once the alleged leaker, Private Manning, had passed the cables to Wikileaks, they were everywhere, and impossible to put back in the bag.

Data on the internet exists in only one of these two states, cursory openness or total secrecy, but real life is full of shades of gray. We tell things to our family we would not tell to our friends, which we would not tell to colleagues, which we would not tell a stranger on the bus and so on. Ultimately, without the privacy of out thoughts, the self as we know it would not exist. What Lanier fears is that Wikileaks, in seeking absolutely transparency, will instead create the opposite, a completely militarized state where information is tightly controlled. For fear of losing the crown gems of military secrets, the government might lock everything up.

For Bruce Sterling, Wikileaks and its founder are the physical and political embodiment of the Internet, of a hacker culture that delights in the coolness of information and access without much worry for the real consequences. There is a hacker belief in the power of Truth, and the equation of Truth with a lot of information. But for ordinary people, not computer nerds or hackers, information is blinding light, bleach that destroys privacy and personality. The opposite side of transparency in democracy is discretion, the ability of the public servants to speak only so much of the truth, because the whole truth will lead to chaos, not freedom.

That is the essence of what Wikileaks has done to American diplomacy in the wake of Cablegate. I doubt that there is much surprise in professional diplomatic circles over the contents of the tables. The corruption and lasciviousness of world leaders makes for fun gossip for the chattering classes, but the most likely result is that foreigners will be leery of sharing their candid assessments with American diplomats, and diplomats will be worried about sending those assessments on. Mutual griping, gossiping, and speculating is required to build informal communities of trust (or authoritarian conspiracies), and cannot be sustained when diplomats must examine every word for its public significance, not just the joint statements made at the end of prolonged negotiations. The sphere for public thought and action has drawn smaller.

I keep faith in the hacker credo that information is power, that information wants to be free, and that information can set us free. But Wikileaks is only the first step; information must be used by people to impact the world. Wikileaks itself has become more canny about this in its four year history, strategically providing the most provocative documents to the mainstream media first, but a brief flurry of indignation over the state of the world is not a solution. Even with their corruption exposed, most of the people featured in the Wikileaks cables are effectively beyond the reach of the law. Wikileaks espouses one way of dealing with them, based on shame, paranoia, and ever escalating cyber-attacks. But shame is only relevant in the eye of an increasingly jaded and distracted public. Paranoia effects the institutions we rely on as much as it effects malefactors, and cyber-attacks are a dead-end arms race that will only make computers and networks less useful.

Rather than the antagonize the world, as Wikileaks and those in government charged with responding to it have done, we should use this chance to have a conversation, not a trial. The US government should publicly make the case why its actions in exposed by Wikileaks have been for the good of the nation, and the world. And if your arguments cannot withstand public scrutiny, then it is time to find new policies, and new goals. What we need is not transparency, but candor.

20101220

Soylent Gas is People

This being from a drunken conversation last night, about renewable energy.

20101212

OpenMaterials.org

OpenMaterials.org is a pretty nice website. Their blog is a nicely curated mix of science, art, hacking, and sustainability. I want to re-link a lot of the stuff they've covered, but you can head over and check out their website in full. Here are the top five cool things that I didn't know existed before today :

20101208

Bayesian hallucination

- let $u$ be the utility ( benefit ) of responding to a notification,

- let $c$ be the cost of verifying whether a notification is real or imagined

- let $\Pr(\mathrm{present})$ be the probability that a notification is really there

[0] $\mathbb E(u) = u \cdot \Pr(\mathrm{present})$

[1] check notification if and only if : $u \cdot \Pr(\mathrm{present}) > c$How does one know $\Pr(\mathrm{present})$ given some unreliable observation $\theta$ in peripheral vision, that is $\Pr(\mathrm{present}|\theta)$ ? This can be computed using Bayes' theorem : [2]

[2] $\Pr(\mathrm{present}|\theta)=\Pr(\theta|\mathrm{present})\cdot\Pr(\mathrm{present})/\Pr(\theta)$So, $\Pr(\mathrm{present}|\theta)$ is the probability of observing $\theta$ when the notification is really there, $\Pr(\theta)$ is the probability of observing $\theta$ overall, and $\Pr(\mathrm{present})$ is the background probability of the notification being present. Plugging in expression [2] for $\Pr(\mathrm{present}|\theta)$ into equation [1] :

[3] check if and only if : $u \cdot \Pr(\theta|\mathrm{present}) \cdot \Pr(\mathrm{present}) / \Pr(\theta) > c$

Why Scientists Aren't Republicans

Dan Sarewitz writes one of those articles about something that we all know, and that should prove terrifying.

Dan Sarewitz writes one of those articles about something that we all know, and that should prove terrifying.

Could it be that disagreements over climate change are essentially political—and that science is just carried along for the ride? For 20 years, evidence about global warming has been directly and explicitly linked to a set of policy responses demanding international governance regimes, large-scale social engineering, and the redistribution of wealth. These are the sort of things that most Democrats welcome, and most Republicans hate. No wonder the Republicans are suspicious of the science.

Think about it: The results of climate science, delivered by scientists who are overwhelmingly Democratic, are used over a period of decades to advance a political agenda that happens to align precisely with the ideological preferences of Democrats. Coincidence—or causation?

Of course, Dan's a political thinker, an iconoclast, a bridge-builder. He goes on to advocate that scientist endeavor to show that they are not mere political shills to conservatives. Scientists have an immensely trusted position in American society (above 90%), and it'd be a shame to throw that away.

I prefer to take the opposite tack. What is it about Republican politics that is anti-science? Could it be that conservative positions on the environment, public health, economics, national security, and the origins of the universe are so obviously counter to reality that no-one who considers themselves both a Republican and an astute observer of a real, physical universe? The level of cognitive dissonance required to maintain both literacy with the frontiers of science, and adhere to conservative ideology is completely unsustainable.

Even more deeply, perhaps there's something implicitly antagonistic about science and conservatism. Science relies on a belief that truth is contingent on What Is, and What Can Be Observed. It does not matter who postulated a theory, as long as it matches reality. And if a theory fails, then it, and all contingent facts should be discarded. Conservatism, the worship of the past and a desire for stability, is antithetical to this project of continually tearing down and rebuilding reality.

Perhaps a better question is: Given that the world today is scientifically and technically constructed, that scientific truths are the 'best' truths, that technological artifacts define our lives, why should we listen to a group which is so fundamentally anti-science?

Not everything is relative. Sometimes there are right answers.

A note on the binding problem

Edit : never-mind, this post is redundant to this much more comprehensive review.

Edit : never-mind, this post is redundant to this much more comprehensive review.

To simplify, say you are presented with a spoon on the right and a fork on the left, and asked to retrieve the fork. So, somewhere in the brain is the notion "there are two things here, one on the left and one on the right" and somewhere else in the brain is the notion "there is a spoon and a fork here, but I'm not sure where". How the brain combines these two representations has been the subject of much speculation.

Some have proposed that populations of neurons responding to the same object become synchronized, such that neurons firing for "thing on left" and neurons firing for "fork somewhere" tend to fire at the same time, and this somehow unifies the two areas. I am skeptical of this "binding by synchrony" hypothesis.

I am skeptical because, when I am not paying attention, I am very likely to pick up the wrong utensil, and I suspect that attention is critical for binding. This argument hinges upon some assumptions of how the visual system works and what attention is.

The visual system is hierarchical. At first, the brain extracts small pieces of lines and fragments of color. These features are well localized, and "low level". Then, the brain begins to extract more complex features. These may be corners, curves, textures, pieces of form. This information is not as well localized. The combining of features into more complex features is repeated a few times, until you get to "high level" representations complex enough to identify whole objects, like "forks" and "spoons". As features get more complex, they loose spatial precision, until the where neurons that can identify objects really have no idea where that object is.

In the visual system, there is feed-back from higher level to lower level representations. Activity in high level representations can bias activity in lower level representations. You may be most familiar with this phenomena when you are day-dreaming. We are able to control, to some extent, the activity in most visual areas, and we thing that this control constitutes imagination. We have more control over "high level" visual areas. This control weakens toward lower level visual areas. For instance, primary visual cortex appears to be inactive in dreaming and visualization.

When we are awake, this top-down control is used for attention. Attending to an object will make said object "pop out" ( become more salient ). This enhanced salience may propagate from higher to lower level visual areas. For instance, if I focus on "fork!", the neurons that know there is a fork somewhere will enhance all fork-like mid level features, which will enhance fork-like low level features, and so on.

The key point here is that, by focusing on the identity of an object, I can increase the salience of low and mid-level visual features representing that object. Although the semantic part of my brain may have no idea where the "fork" is, it can make the low-level fork features pop-out. And, these features are well localized. Thus, the part of my brain that knows "there is something on the left, and there is something on the right", will find that the item on the left suddenly seems more salient. This seems sufficient to let the brain know where it needs to reach to pick up the fork.

This effect works both ways. If I ask "what is the object on the left", the neurons that know where the thing on the left is will make the features of the left object more salient, which will enhance the representation of the "fork" features in the part of the brain that can identify what objects are. Note that this effect doesn't need to be large, or make the "fork" dominate over all other objects in the scene. You simply need a brief increase in the salience of "fork" over background objects to know that the thing on the left is a "fork".

All of this happens rapidly and automatically. Binding is achieved by attending to high-level properties of objects, and therefore gating which objects get processed in other, distant, high-level areas. Attention ensures that at a given time only one unified object is most salient.

Posted by

M

at

8.12.10

0

comments

![]()

Labels: attention, binding problem, neuroscience, speculation

20101206

Report from Transforming Humanity

This past weekend (Dec 3-4), I attended the Transforming Humanity: Fantasy? Dream? Nightmare? Conference hosted by the Center for Inquiry, Penn Center for Bioethics, and the Penn Center for Neuroscience and Society. James Hughes and George Dvorsky of the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies give their blow-by-blow record of the conference, but I'd like to step back and provide an overview of the field, and its position today.

This past weekend (Dec 3-4), I attended the Transforming Humanity: Fantasy? Dream? Nightmare? Conference hosted by the Center for Inquiry, Penn Center for Bioethics, and the Penn Center for Neuroscience and Society. James Hughes and George Dvorsky of the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies give their blow-by-blow record of the conference, but I'd like to step back and provide an overview of the field, and its position today.

The ability to use pharmaceuticals, cybernetics, and genetic engineering to alter human beings poses many complicated ethical, philosophical, and political issues about the potential deployment of these technologies. The attendees at the conference ranged from hardcore transhumanists, to left-wing bio-conservatives, and took a variety of approaches, from theology, to philosophy, to bioethics and medical regulation.

On the philosophical side, several speakers traced the philosophic heritage of transhumanism, and the demand to either find a place for man in the nature world, or the necessity of creating a unique standpoint, through the works of Thoreau, Sartre, and Cassirer. Patrick Hopkins of Millsap College gave an interesting lecture on a taxonomy of post-human bodies, Barbies, Bacons, Nietzsche, and Platos. Post-humans will have to find internal meaning in their lives in many ways, and while I appreciated the scholarship, there should have been more about the new intimacy of technology to the post-human, and its effects on daily life, beyond the obligatory references to Harraway's Cyborg Manifesto.

On the practical side, the Penn contingent (Jonathan Moreno, Martha Farah, and Joseph Powers) talked about coming developments in cybernetic devices, brain implants, and pharmaceuticals. As it stands, there exists no regulatory framework for enhancements. The FDA will only certify the safety of therapeutics, drugs that treat diseases, which means that a prospective enhancement will either have to find disease (medicalization, in the jargon), or exist in a legal limbo. Katherine Drabiak-Syed gave a great lecture about the legal and professional risks that doctors prescribing Modafinil off-label run. Despite American Academy of Neurology guidelines approving neuroenhancement, prescribing doctors are putting their patients at risk, and are violating the Controlled Substances Act.

Allen Buchanan opened the conference by suggesting that there was nothing special about unintended genetic modification, or evolution, while Max Mehlman of Case Western closed the conference by asking if humanity can survive evolutionary engineering. Dr. Mehlman posed four laws: Do nothing to harm children, create an international treaty banning a genetic arms race, do not exterminate the human race, and do not stifle future progress for understanding the universe. Good principles, but as always, the devil is in the details. International law has been at best only partially successful at controlling weapons of mass destruction or global warming.

To close on two points: The practical matter of regulating human enhancement remains highly unsettled, and leading scholars in the field are only beginning to figure out how we can judge the effectiveness and risk of particular enhancements on a short-term basis, let alone control long-term societal changes. The potential creators, users, and regulators of enhancement are spread across medicine, electrical engineering, law, education, and nearly every other sector of activity, and they are not communicating well. Basic questions such as “What does it mean to enhance?” and “Who will be responsible?” are unlikely to be closed any time soon.

On a philosophical level, the question of whether “To be human is to choose our own paths,” and “To be human is to find and accept your natural limits,” is unlikely to have a right answer. But Peter Cross was correct when he pointed out that even enhanced, humans will still need to find a source of meaning in their lives. If there is a human nature, it is to be unsettled, to always seek new questions and answers. The one enhancement we should absolutely avoid is the one that will make us content.

Posted by

Michael BF

at

6.12.10

2

comments

![]()

Labels: science, society, technology, transhumanism

20101201

Belief-based certainty vs. evidence-based certainty

Over at [this] foum I noticed the following comment #10, which plays into some recent thoughts I've been having :

Over at [this] foum I noticed the following comment #10, which plays into some recent thoughts I've been having :"Evidence-based certainty uses rationality to gradually prove or disprove theories based on empirical evidence. Belief-based certainty works in the other direction, the desired certainty is already known and rationality is abused to build on carefully selected evidence to “prove” that belief.I think in a very broad sense the narrative which "RFLatta, Iowa City" is drawing, and which Paul Krugman often uses to distinguish himself from those dastardly freshwater economists, is true, but should be taken with a grain of salt because it is a false dichotomy.

Belief-based certainty will always have a higher value socially and politically in the short term because it satisfies the immediate need for certainty and it is purchased by those who have the assets to afford it and have the most to lose.

Evidence-based inquiry is a process that only produces a gradually increasing probability of certainty in the long term. Facts will lose the news cycle but quietly win the cultural war."

"Evidence-based inquiry" is surely what we ultimately want to point to when we talk about science and mathematics, but the process of how the sausage is made is obviously different in some important respects. An investigator knows he must collect evidence, but what are the right questions to ask? What are the right experiments to perform? These decisions cannot be made on the basis of hard evidence, since we haven't collected any hard evidence yet -- one must take existing hard evidence from other's experiments and then try to extrapolate to make a plausible prediction.

Indeed in computational learning theory too, we see the importance of this approach of "finding a plausible fit" to some of the data based on some unjustified assumptions, and then testing the hypothesis against other data.

The point is, we can't find a good fit until we understand the data, but we have to start somewhere, so where do we start? The answer is, generally, we start with our beliefs, and go with our gut.

In mathematics of course, having a good intuition is critically important. Famously for Godel, intuition was all important -- even though the Continuum Hypothesis is known to be independent of ZFC, Godel believed we can have set theoretic intuition about some of its consequences such that we should reject it as false. How Godel could possibly have cultivated such an intuition continues to be regarded as something of a mystery, depending on how much you read into it. Richard Lipton writes a nice blog post about all of this: http://rjlipton.wordpress.com/2010/10/01/mathematical-intuition-what-is-it/

Which brings me to a critical juncture -- what is the distinction between intuition and prejudice? My contention is that there is none, they are semantically equivalent and differ only in positive / negative connotation. I should mention another quote I am fond of which I may have disseminated previously:

"A great many people think they are thinking when they are merely rearranging their prejudices." -William JamesHow do we know when we are really meaningfully investigating an open question as opposed to just juggling around our prejudices? It really seems that at least some of the time, this may be the hardest aspect of science. I can certainly remember advisors on projects I worked on in the past who were pleased when, I lead myself to backtrack on some entrenched assumption I had made.

How do we confront issues like this when the question is something like P vs. NP, where now essentially 90% of the field believes P != NP, and takes the attitude "we know they aren't equal, now we just have to prove it"? In at least one talk I've seen, Peter Sarnak stuck his neck out and opined that this attitude is unscientific.

It seems to me that most of the time, we don't spend too much time arguing about intuitions, because it is largely unproductive. Use whatever mystical value system you want to guide your research, but if it doesn't produce results, you'd better toss it out the window, and it must yield to proofs. It's fine to believe "P != NP because everything is an expander graph", and get it tattooed on yourself in German if you want, but if it doesn't go anywhere... don't get too attached to your burdens.

So whats the moral? At this point, it seems to me that, mathematical intuition is a total myth, part of this silly hero worship ritual that we all seem to indulge in to some extent. Yet on the other hand, I've never known professors to disabuse undergrads or grad students of this idea. Indeed we even see really famous people like Godel, Richard Lipton, and Enrico Bombieri "indulging".

So perhaps as a reasonable hypothesis is that, we progress as follows -- when we are young we believe anything, when we are grad students, we become dramatically more skeptical, and then somehow with experience, we come around and believe again.

I just spent like 20 minutes trying to find this webcomic I believe I saw like this... it was either xkcd or smbc, one of these things where you have a graph showing how, either with age or amount of thought put into it, your belief in God begins very high, then plummets "how could god possibly exist", and then continues to oscillate between 50% and 0 for the rest of your life "oh that's how...".

Personally I don't find that to be the case wrt God, but I now think its plausible with respect to mathematical intuition.

And there we go again, extrapolating some kind of crazy oscillating curve based on two data points, some hearsay, and a web comic... fml.

Posted by

Beck

at

1.12.10

2

comments

![]()

Labels: belief, decision theory, knowledge, science, society

20101121

Fractals

The folks at fractalforums.com have been rendering more of those crazy alien-cyborg-city-spaceship ray-traced fractals. I don't understand their algorithms but their "mandelbulb" software is free for download. Perfect for zoning out for a little brain-massage.

And I thought I was just going to pop over to youtube to grab this little wheel illusion video. The fractals are much more entertaining.

Posted by

M

at

21.11.10

0

comments

![]()

Labels: fractalforums, fractals, graphics, mandelbulb, omgfractals, ray-traced

20101118

retweet

Hope I'm not opening pandora's box by retweeting Paul Krugman, but I really thought this was a gem.

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/11/18/cheese-eating-vat-paying-surrender-monkeys/

20101110

Rapid Prototyping ≠ Digital Reproduction

Most plastic objects we encounter day-to-day have little value added beyond their actual physical manufacturing cost. As long as mass production remains more efficient for plastic parts, there should be enough of a gap between the cost of home printing and the cost of an industrially produced item to discourage piracy. I understand that this is oversimplified : there may be objects that have artificially enforced scarcity, by copyright and patents. However, I just can't remember running into such an object, built only out of plastic, in recent memory. Design patents are still an issue, but these do not limit functional reproduction, only aesthetic.

I'm obviously overlooking some things. For instance, a 3D printer that could operate on recycled materials just might undercut mass production. However, there is still an upper limit to how much thermoplastic you want piling up in your house. If you had to physically print out every article you wanted to pirate, your study would rapidly fill with articles and papers ( and indeed, many of our office are such masses of papers ). At some point you'd realize that the cost of all that toner might not really be worth it.

Of course, you might get a situation where people pirate objects, print them, use them for a time, and then recycle them back into feedstock. But, what would have been the fate of the same objects had they come from industrial production ? Overwhelmingly, they would be destined, like so much of the rest of the 20th century, for our landfills, garbage islands in the Pacific, and the stomachs of (dead) albatrosses. The only way rapid prototyping could become a sustained threat to manufacturing is for rapid prototyping to become both sustainable and a viable means of manufacturing, of which it is neither at this time.

I feel that there is some sort of intrinsic efficiency gain to mass production that will always discourage piracy of printable objects, but I would also love to be proved wrong in this assumption. If or when printing technology matures to this point, well ... heh ... they'll never be able to stop us anyway.

p.s. : but seriously, the paper is good and basically a completely accurate, way better analysis, than this post. so, head over there.

Posted by

M

at

10.11.10

6

comments

![]()

Labels: 3D printing, copyright, MakerBot, manufacturing, post scarcity, whateveritsjusttheinternet

20101109

Pseuductivity

We define a new notion of Pseudoproductivity, which we call Pseuductivity. We leave it to the reader to mentally fill in the rest of the page with pseuductive blather....

20101024

Flash Fiction

The New Scientist has a Flash Fiction contest. The topic is "futures that never were." Maybe the geniuses at We Alone have 350 words.

This week, New Scientist goes in search of lost classics of science fiction – brilliant books that could stand alongside The War of the Worlds andNineteen Eighty-Four as masterpieces of speculative literature, but have somehow or other lapsed into obscurity. Each is a forgotten vision of the future.

Now we'd like to read yours. Send us your very short stories about futures that never were. Tell us where we'd be today if the ether had turned out to exist after all, or if light really was made up of corpuscles emitted by the eyes. You don't have to be scientifically accurate, but the more convincing your story, the more likely it is to win!

20101021

20101020

Ramblings prompted by Bruce

You should all read this interview with Bruce Sterling. Full of tasty nuggets on global warming, fiction writing, futurism, Google, other cultures, Texas, science funding, morality.

You should all read this interview with Bruce Sterling. Full of tasty nuggets on global warming, fiction writing, futurism, Google, other cultures, Texas, science funding, morality.

Rhys: The great Italian writer Primo Levi, who was an accomplished chemist, came to believe that research for the sake of research was fundamentally immoral and that individual scientists should remove themselves from fields of inquiry that might prove potentially hazardous to the human race. Is such a moral approach even possible?

Bruce: Not really, no. That's not practical. Individual scientists have no ability to remove themselves from their sources of funding, and to remain scientists. Governments, academies and major corporations fund their fields of scientific inquiry. Individual scientists do not have any veto power there.

When American politicians told scientists that stem cell research was immoral, the scientists grew indignant. Stem cell research is indeed potentially hazardous to the human race. It's a fact, but scientists don't like to be told that. They launched a counter-campaign to establish that the ban itself was immoral. These scientists were not being cynical. There are good moral arguments for conducting stem-cell research.

Scientists have never been morality experts. Scientists are naive about morality, no better than other technicians such as programmers or engineers. Philosophers and theologians are our cultural experts about morality. These moral experts can argue for or against almost any moral stance, convincingly. Two moral philosophers in a room will always quarrel. Two moral theologians in a room will kill each other.

They would kill Primo Levi, if they could capture him.

Posted by

Michael BF

at

20.10.10

0

comments

![]()

Labels: bruce sterling, climate change, conversations, vision

20101019

The Immortals

Yesterday, I visited the Immortals. I abandoned my car at the periphery wall, no vehicles are allowed inside the Old City, lest immortality be cut short by accident. The narrow streets were packed with shuffling, cautious forms, cast into darkness by the overhanging extensions and expansions of the longevity hospitals, their needs for space long impossible to meet on the ground.

Yesterday, I visited the Immortals. I abandoned my car at the periphery wall, no vehicles are allowed inside the Old City, lest immortality be cut short by accident. The narrow streets were packed with shuffling, cautious forms, cast into darkness by the overhanging extensions and expansions of the longevity hospitals, their needs for space long impossible to meet on the ground.

Posted by

Michael BF

at

19.10.10

3

comments

![]()

Labels: conversations, evolution, fiction, future, immortality, philosophy, science fiction

20101015

20101013

20101010

This is Why We Roll

Two of the players in my ASUDND game have posted some great thoughts on their experience with RPGs so far (MK and John), and I feel it's only fair to post mine. Why do we play games? Because they're fun. And why are they fun? When RPGs work, they combine the best parts of the narrative experience of a good novel, the tactic cut-and-thrust of a skirmish wargame, and the social pleasure of hanging out with people you like.

Two of the players in my ASUDND game have posted some great thoughts on their experience with RPGs so far (MK and John), and I feel it's only fair to post mine. Why do we play games? Because they're fun. And why are they fun? When RPGs work, they combine the best parts of the narrative experience of a good novel, the tactic cut-and-thrust of a skirmish wargame, and the social pleasure of hanging out with people you like.

Narratives are the heart of the RPG. What kind of story do you want to tell, what themes, what stakes, what characters? For a GM, the tension is between a tightly plotted story, and the sandbox, where the character explore a broader world. ASUDND is a sandbox, I've created a very sketched out island populated by prospectors, goblin tribes, mysterious ruins, and mercenaries, and let the characters seek their own paths.

The standard D&D story is half-way between Campbell's monomyth, and a heist movie, where a team of skilled professionals is a given a quest, completes it through the strategic use of violence, and is rewarded with power and another quest. Eventually, you go from nobody to plane-shaking god-slaying superpower. This model works well enough, but gets a little tiresome. Great gaming enables players to establish a character, then places that character in a situation of actual conflict, where their preconceived notions of morality and loyalty break down. As I put in the teaser for my play-by-post game, Under No Banners, “What do you believe, and how far will you go for those beliefs?” I want to create a world that lets ambitious people seek excellence, and puts those ambitions in conflict with each other, and with something larger.

To describe where ASUDND stands, the Emerald Regiment has put their plans of capitalist-imperalist domination on hold to deal with a personal feud with an NPC group doing many of the same things they've done. To accomplish this, they've allied with the goblin tribes against their previous employers. But every action has consequences: goblins can't pay for mercenaries, and the Regiment has made a stand against everything that Port Arthur stands for. Where will they go from here? I would say that the past few sessions have been practice, this is where the adventure really starts.

The second part of the game is the system. Both of my players mention some dismay at their pregenerated characters. I personally find D&D4e a lot of fun as a tactical wargame, regardless of the roleplaying, which means that part of my job as DM is to teach new players how this game works. Character creation should be a collaborative process between a player and the rest of the group, usually mediated by the GM. In this case, because I have so much more power due to my knowledge of the rules, and D&D character building software, I've appropriated a lot of that process, translating a rough description of the character that the player into the language of the D&D4e ruleset. This is not how the game should work, and I hopefully won't have to do it again. Conversely, I need to shape up my encounters, making them more balanced, interesting, and treasure-filled.

I could talk more about ludic circles, or cultural models, or finite and infinite games, but I've found that RPGs are delicate creatures, and the tools of academic discourse usually just mangle them, like deep sea fish being brought to the surface. Forget the theory, Gary Gygax has The Wisdom.

"The ultimate success of this adventure in your campaign, rests upon you, the DM. It is you skill and knowledge not only of the adventure and the AD&D rule system, but of your players as well, that determine how enjoyable your games with this adventure are, There is no "right" way to run any encounter. There is only your way to of running encounters. You may add or delete from the story as you see fit. What is contained within is only a skeleton, it is your input that makes it a worthwhile adventure".

"You are not entering this world in the usual manner, for you are setting forth to be a Dungeon Master. Certainly there are stout fighters, mighty magic-users, wily thieves, and courageous clerics who will make their mark in the magical lands of D&D adventure. You however, are above even the greatest of these, for as DM you are to become the Shaper of the Cosmos. It is you who will give form and content to the all the universe. You will breathe life into the stillness, giving meaning and purpose to all the actions which are to follow."

"The secret we should never let the gamemasters know is that they don't need any rules."

Indeed.

20101008

Those Climate Scientists Deserved It, Acting All Smart Like That

Roger Pielke Jr always has something interesting to say about climate change, and today's post about the politicization of climate science was no exception. Piekle refers to a recent article in National Journal that “Nineteen of the 20 Republican Senate nominees who have expressed an opinion on the widespread scientific consensus that greenhouse gases are altering the world's climate have declared the science either inconclusive or dead wrong, often in vitriolic terms.” Piekle notes that policy has become increasingly hyper-politicized, there's nothing inherently 'conservative' about not believing in global warming, except as a badge of tribal identity. Reconstructing how climate science came to be viewed in such a politicized light would be an interesting exercise, but as it related to contemporary issues, Pielke calls for a de-politicization of climate science. Referring to an editoral by Michael Mann about the Climate-gate emails he says:

Roger Pielke Jr always has something interesting to say about climate change, and today's post about the politicization of climate science was no exception. Piekle refers to a recent article in National Journal that “Nineteen of the 20 Republican Senate nominees who have expressed an opinion on the widespread scientific consensus that greenhouse gases are altering the world's climate have declared the science either inconclusive or dead wrong, often in vitriolic terms.” Piekle notes that policy has become increasingly hyper-politicized, there's nothing inherently 'conservative' about not believing in global warming, except as a badge of tribal identity. Reconstructing how climate science came to be viewed in such a politicized light would be an interesting exercise, but as it related to contemporary issues, Pielke calls for a de-politicization of climate science. Referring to an editoral by Michael Mann about the Climate-gate emails he says:

“Do Mann and the climate science community actually think that directly linking battles over climate science to upcoming national elections will depoliticize climate science?!

Not only does the public get the politicians that it deserves, but it seems that climate scientists get the politics that they deserve as well. Until the scientific community shows some willingness to take actions that reduce rather than reinforce the political intensity of the climate debate, they are acting as willing accomplices in its hyper-politicization.”

Really, Dr Pielke? Should climate scientists just lie back and take the “vitriol” in the hopes that global warming will stop being a political football? I believe that Piekle is trying to recover a model of science and the state that no longer applies. As Sheila Jasanoff explains, the contract of post-WW2 American science was that the state would supply funding to scientists, and scientists would supply knowledge to legitimate the decisions of the state (Jasanoff, Technologies of Humility: Citizen Participation in Governing Science, 2003) This contract was rendered void by 1990 because of deviant science (see David Baltimore and AIDS), political demands on scientists to legitimate regulations on objects that were poorly defined, like microparticulates and GM foods, and the growing awareness by scientists of the political and social implications of their work.

We can't turn back time to those halcyon days of the early Cold War, so what now? The choices break down into more involvement, or less. Scientists could decide that certain topics are too politically risky to investigate. I believe this course to be a bad one, as the realm of the non-political is microscopic, perhaps only the most abstruse areas of theory are free of politics. And even if scientists relinquish politics, the demand for expert knowledge is too ingrained in American democracy. Whether they want it or not, scientific knowledge will be used and misused by politicians.

The alternative, engagement, is highly risky. It requires the organization of scientists as political actors, from a national to local levels. It demands the scientists act as a class to bestow and withhold the favor of expert knowledge on their representatives. When you play the game, you might win, but you also might lose. Scientists could find their fortunes tied to one party, and a host of issues completely unrelated to science. They could find themselves on the losing end of an economic downturn, or a culture war, guilty by association.

By their words and actions, Republican candidates across America have rejected the favor of science, so what interests do scientists have in supporting them? Let them rule from the gut, let's see how far they get in a society that no matter how much it denies it, relies on scientific knowledge. But from here, scientists face an even more momentous choice. Tactically, their only allies are the Democrats, but Democrats are only marginally more credible on scientific issues. Thomas Friedman (420 Drink KoolAid EVRYDAY) says that we're primed for the rise of a third party. Does science have sufficient credibility and unity to form the core of that party?

20101005

BIG UPS!

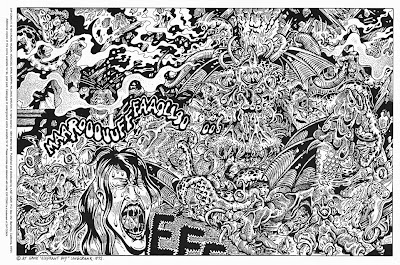

fig.A - Big Ups #1 back cover - "Our Hero" (stop staring.)

"Pop culture used to be like LSD – different, eye-opening and reasonably dangerous. It’s now like crack – isolating, wasteful and with no redeeming qualities whatsoever" --Peter Saville

Big Ups is a way of pushing the context of comics. At first its a simple gesture - email your friends, get some really great art together, put it in a hand made book, release a cd with it, and get it out there one way or the other. On the other hand, the simple, do it yourself nature of it all is more political, I think, then saying, outright, "this is a political gesture". The diversity of the art married to the simple fact that "comics are what make you smile" - what does that mean for kids who want to see something different? For us, I think the unexplainable is way more fun then a one-liner telling you where to go.

This is where we turn to the back cover, featuring a stylish headshot of our hero, Glenn Beck (see fig. A). It's a simple experiment involving an obviously bad political influence (in the sense that he's simply obtuse), transformed into a mandala-like shrine to obfuscation of priority. That's why its going on the back cover, unexplained, utterly beautiful and strange - it represents a 'beyond' of political discourse. The image itself is simply entertaining, but also confusing as hell. The act of fucking with an image of Glenn Beck (or Bill O' Reilly, or Jon Stewart, for that matter) is like burning an effigy that looks nothing like the subject. Plenty of people want to lay into Our Hero for being an idiot, but personally I don't have time to even concern myself with the nonsense that leaves his mouth. In other words, the mere act of transforming a likeness of Glenn Beck into a psychedelic icon/monster is an exercise in political discourse that aims to make political discourse obsolete. It represents the purpose of Big Ups, or anything anyone makes themselves - it demonstrates that we're doing just fine with or without Our Hero.

Peter Saville's apt quip reverse engineers the idea nicely - essentially we are taking crack-like pop culture and turning it into a moderately valuable form of cultural LSD, in that it is different, it is confusing, it is associated with the practice of creating situations for yourself again, rather than having it mindlessly sold to you.

Underground comics in the sixties and seventies did this all the time - ZAP! for example (see Fig.B), was famous for it, making drug references seem as common as breathing, and featuring horrifyingly(and entertainingly!) detailed graphic scenes of sexual and/or violent natures (Fig.C), or art that was too confusing and gruesome and difficult to be considered acceptable by the mainstream (Fig.D). It was art that sought beauty where others saw filth. It was art for people who got it - anyone who didn't was encouraged to expand their consciousness to do so, or get the fuck out. MAD magazine/National Lampoon were also famous for doing stuff like that, but they also took the more hard-hitting, easy to understand route, making direct parodic shots at political figures, pop culture icons/events, etc. that the mainstream could latch onto more easily. I'm partial to stuff like ZAP! for the very reason that it made no sense whatsoever. It reminds me that life is a little more complicated than following people like Glenn Beck on their journey towards ultimate stupidity.

Underground comics in the sixties and seventies did this all the time - ZAP! for example (see Fig.B), was famous for it, making drug references seem as common as breathing, and featuring horrifyingly(and entertainingly!) detailed graphic scenes of sexual and/or violent natures (Fig.C), or art that was too confusing and gruesome and difficult to be considered acceptable by the mainstream (Fig.D). It was art that sought beauty where others saw filth. It was art for people who got it - anyone who didn't was encouraged to expand their consciousness to do so, or get the fuck out. MAD magazine/National Lampoon were also famous for doing stuff like that, but they also took the more hard-hitting, easy to understand route, making direct parodic shots at political figures, pop culture icons/events, etc. that the mainstream could latch onto more easily. I'm partial to stuff like ZAP! for the very reason that it made no sense whatsoever. It reminds me that life is a little more complicated than following people like Glenn Beck on their journey towards ultimate stupidity.(note - please see fig. E for the Big Ups back cover's direct inspiration)

20101001

A Portrait of the City as a Squiggly Line

This is very much à propos of none of the grand debates about the future. It can hardly be, because urban form is necessarily so static, so hard to change, so grounded in heavy expensive physical bricks. It's something we're pretty much stuck with whatever else happens.

A recent post on transit consultant Jarrett Walker's blog Human Transit discusses why it's misleading to talk about the average density of a city or urban area. There are other factors, but mainly it's misleading because the average tells us nothing about the shape of the curve, and also because it averages over land area when, in trying to decide policy, we ought to think about what affects the most people.

The US Census Bureau defines urban areas by taking a city center and eating up adjacent blocks until it reaches areas that are not built up (or another urban area.) The blocks that are included are contiguous blocks with density at least 1000/sq. mi. and adjacent blocks with density at least 500/sq. mi. Such an area will include both high-rises and suburbia, and the average density (which the Census Bureau provides) tells us nothing about urban form. For example, it rates Los Angeles as more dense than New York, which is obviously misleading. Nevertheless, as we shall see, our prejudices are also often misleading, and more detailed and meaningful numbers can help us adjudicate between the two. So I downloaded some data from the 2000 census and made the following graphs, whose x-scale is pleasingly logarithmic:

There are a number of things that stand out in this graph, both obvious and surprising. Without much prejudice as to which is which, here are some of them.

- The densities of older cities (New York City, Chicago, and Boston) are essentially bimodal, with a dense, older urban core surrounded by low-density suburbs built up after World War II, although Boston's curve is oddly flat. The densities of newer cities are essentially unimodal. Everyone in LA lives at broadly the same density -- it's no accident even Italo Calvino called it a city without form.

- About 7 of the 18 million people in greater New York City -- the vast majority of whom form much of the population of the city proper -- live at densities that are home to only about 5% of LA, the Bay Area, Boston and Chicago.

- On the other hand, LA's curve is pretty much uniformly higher than Chicago's; for any given density, there are more Angelenos living above it than Chicagoans. This is worth dwelling on because most people think of Chicago, and not LA, as a Real City with tall buildings. I suspect I know the reason for this. The densest parts of Chicago are the Loop and the lakeshore on the North Side; these are also the most affluent, most-visited, most touristy parts. On the other hand, the touristy, impressive, upscale parts of LA are spread all over the place, and are mostly not in the densest parts, which are the areas just east and west of Downtown as well as South Central, that place whose condition is so shameful they gave up and renamed it to South LA. (Hollywood is also very dense, but, outside the famous bits, also rather poor.) Even if you live in a city, you are mostly a tourist outside your own neighborhood, and so the parts you see are unrepresentative. "[Y]our stereotype of Los Angeles may be a ranch-style house with a big pool on a cul-de-sac," writes Jarrett; indeed, we think of LA as low density because when we think of a city we first think of its sparkly rich parts. (I kind of exclude myself from this 'we' since I like to grub around in ethnic neighborhoods, but it still applies to some degree.)

This also makes me suspect that the best public transit model for LA would be the one that Chicago uses: rail lines that go to most places, but not necessarily from everywhere to everywhere, and faster, better buses. This seems to be what is already happening, but it will require free transfers and higher frequencies off-peak to make it really convenient. - While the most common density for the other Western cities is between the two peaks of the Eastern ones, Seattle, despite its hipster image, seems to pretty much be a sea of sprawl; it has a single peak which is around that of New York and Chicago's suburbs.

- Atlanta deserves its reputation as a sprawl capital. Not only does it entirely consist of low-density suburbs, but those suburbs are actually considerably lower-density than those of other cities.

- Las Vegas is middling dense, if you average over the metro area, but amazingly uniform. Half its population lives in densities within a factor of two of each other.

I'd be curious to try this on cities outside the United States, and on more diverse urban forms, but not so curious as to look for the data myself.

Conflicts

"I want to state the following moral principle: If a new technology makes it possible to avoid a conflict between legitimate interests, it is our duty to use the new technology."

"I want to state the following moral principle: If a new technology makes it possible to avoid a conflict between legitimate interests, it is our duty to use the new technology."

--Stellan Welin Reproductive Ectogenesis

Sometimes technological effects change is incremental, other times it is transformative. Making an entire section of moral and ethical conflict obsolete is one of the most transformative uses of technology. Beyond the technical limitations surrounding our lives, we are shaped by the moral character of the debates those technologies engender. Welin is speaking of ectogenesis, incubating embryos outside a female womb, and the abortion debate, but similar issues apply with other technologies. Digital media and intellectual property law is a contemporary case, uploading and physical murder may be one in the future.

Do we have an obligation to bypass conflict with technology?

20100930

In Honor Of

We bought the sky, the greatest ticket the universe had to offer. 100,000 of the best and brightest Terra had to offer. Brave pioneers who sacrificed everything for a chance to make it on new planet, free from the troubles of home. They said we were fools; there was no way to build something that big, that the cryosystems would never work, that our ship would break. They said we were traitors; Earth needed our skills, the resources that went into our ship came out of the mouths of the starving. But we were heroes, out on the grand question for evolution. Some of us died before the work was completed, their children carried on. When the time came, we took the shuttles to geosynchronous orbit, started the fusion Orion/pulse drive, sealed up the cyrochambers, and slept. We dreamed of green fields and blue skies.

We bought the sky, the greatest ticket the universe had to offer. 100,000 of the best and brightest Terra had to offer. Brave pioneers who sacrificed everything for a chance to make it on new planet, free from the troubles of home. They said we were fools; there was no way to build something that big, that the cryosystems would never work, that our ship would break. They said we were traitors; Earth needed our skills, the resources that went into our ship came out of the mouths of the starving. But we were heroes, out on the grand question for evolution. Some of us died before the work was completed, their children carried on. When the time came, we took the shuttles to geosynchronous orbit, started the fusion Orion/pulse drive, sealed up the cyrochambers, and slept. We dreamed of green fields and blue skies.

A stranger opened the cyrochamber door. “Welcome to Eredani Prime. Please present your papers for inspection?” Not an alien, not a pioneer, just the children of those who had take waited for the technology of interstellar colonization to become accessible to the masses. They had brought everything we hated about home with them. We closed the cyrochamber, turned our ship towards the outer darkness, and engaged the main drive.

Fuck physics, and fuck FTL.