Yesterday, I visited the Immortals. I abandoned my car at the periphery wall, no vehicles are allowed inside the Old City, lest immortality be cut short by accident. The narrow streets were packed with shuffling, cautious forms, cast into darkness by the overhanging extensions and expansions of the longevity hospitals, their needs for space long impossible to meet on the ground.

Yesterday, I visited the Immortals. I abandoned my car at the periphery wall, no vehicles are allowed inside the Old City, lest immortality be cut short by accident. The narrow streets were packed with shuffling, cautious forms, cast into darkness by the overhanging extensions and expansions of the longevity hospitals, their needs for space long impossible to meet on the ground.

I met Enos at a sidewalk cafe-clinic, where he was undergoing a routine bloodscrub. Enos was my great-great-great-grandfather, and my sponsor among the Immortals. I leaned down and gave him a peck on the cheek. "How are you, Enos?"

"Well enough. My nanocyte count is down. Perhaps soon they will require replacement. These mechanical parts wear out so quickly." He peered at me suspiciously. Perhaps he did not remember who I was, or why I had come. I had arranged this appointment with his calendar, a time where he was free to talk, but not to leave.

"I've been thinking about what you've said, about what I'll want to do when I come here. I was thinking... art. Nothing big mind you, just some nice virtual landscapes. Exploring the aesthetics of simulated universes." When we had last met, Enos had given me this assignment. What do you want to do when you live forever?

"No, no good." Enos said, languidly waving a hand. "Even we Immortals find our art boring. Simulation spaces are toys, what happens when you grow bored and want to grow up? We have no such thing here."

"But I thought this was what you wanted, nothing big, nothing expensive, nothing that would shake the boat. My simulations are harmless." I said, perplexed.

"Harmless, but sign of else-where, else-whens. There is no else. When the Immortals made this city, they made a covenant with the lifers. Immortality would not be allowed to expanded, it would be to dangerous, would destroy the Earth. Immortality is too small for grand projects. All the time in the universe turns human ambition into dust. No, what you want to do is live. Do you understand what it means to live?"

Philosophy. I was on shaky ground, but I had to advance. "To live is to experience, to grow, the opposite of death. I want to survive forever, Enos, that why I came here."

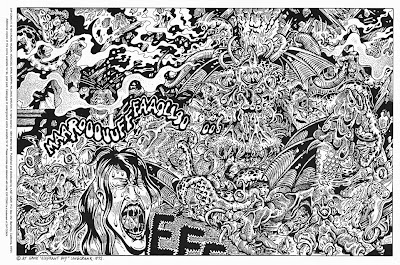

He laughed, a thin sound from a man who conserved his body's strengths. "No, you still don't get it. What we do is exist. Life and death are two sides of the same coin, you cannot have one without the other. I walk, I eat, I see, I exchange pleasantries, but I do not experience in the same way you do, always changing and reacting. Each day is the same as before. Eventually, the sun will expand. I hope to be able to see it, but no more. As long as you want to live, you can never join us. Goodbye, and trouble us no more."

I left, back to the world, back to my hopes, and dreams, and ambitions, such as they were. All I wanted was to live forever, but that is impossible. Nothing that lives can be forever. I turned on my simulations, already they bored me. What a foolish idea, eternity with things such as these, I deleted them forever. We have one life, one brief, finite period in which to laugh and love and dance and live, and when we're gone, so is everything else. I will die, but until I do, every moment, every experience, will be unique. Not like Enos and his eternal sameness till the sun grows and the universe dies.

Yesterday I visited the Immortals.